Tax collections from goods and services tax (GST) have been underwhelming, and the government is set to miss this year’s fiscal deficit target

Mumbai: Widening the tax base and collecting more taxes has been a priority for the current government at the centre. This government’s two major economic disruptions—the introduction of goods and services tax (GST) and demonetisation—were justified in the name of raising tax compliance among other things. However, these moves have not exactly turned out as planned and the government is set to miss its fiscal deficit target for 2018-19.

The Economic Survey released by the finance ministry earlier this year had lauded GST for widening the indirect tax base. The number of indirect tax payers rose by 50% in the first six months of GST implementation, estimated the survey, partly attributable to many small enterprises voluntarily choosing to be part of GST in order to avail input tax credits.

However, even with the wider base, GST collections have been underwhelming. Centre’s total indirect tax collections in the post-GST era shows a marked decline. Indirect tax collections (accruing to the centre) in April to September 2018 grew by only 1.8% from a year earlier, much slower than the 5.6% growth seen in 2017-18 full year and even lower than above 20% growth witnessed in the previous two years.

Prior to GST rollout in July 2017, the centre’s indirect taxes mainly consisted of customs duties, excise duties and service tax, almost in equal proportion. Now, more than 60% of centre’s indirect tax revenue comes from GST.

While indirect tax collections have lagged, direct tax collections have been robust. Evidently, the demonetisation shock in November 2016 did lead to an increase in income tax collections—both from individuals and firms.

However, this increase in tax revenues after demonetisation do not appear to be staggering enough or unprecedented to justify such a large-scale disruption. Part of the increase in direct tax collections in 2016-17, the year of demonetisation, can be attributed to the Income Disclosure Scheme 2016, as an earlier Plain Facts story pointed out.

Further, the rate of increase in direct tax collections post demonetisation has not been entirely unprecedented. The 18% growth rate in direct taxes achieved in 2017-18 was similar to the growth seen in 2010-11.

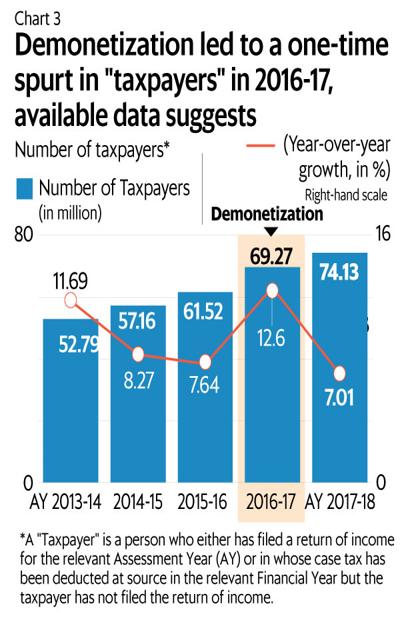

While the number of taxpayers jumped in the assessment year 2016-17, the growth rate fell to familiar levels in the next year.

Thus, it is too early to conclude whether demonetisation has led to any substantial or sustainable increase in tax compliance. The fact that more than 99% of all demonetised notes returned to the system also suggests that the exercise failed to bring much “black money”—i.e. tax-evaded income—into the tax net. This is because only a small portion of tax evasion is carried out in cash.

A January 2018 research paper by R. Mohan and others of the Centre for Development Studies (CDS) estimated that demonetisation could have taken out just 12% of the tax-evaded income in India . While the effects of GST and demonetisation on tax-compliance appear unclear, what is clear is the significant disruption these measures have caused.

Demonetisation disrupted economic activity and hurt growth, especially in areas with high share of informal activity, according to a 2018 World Bank research paper. The paper shows that in districts with more informal activity, local gross domestic product (GDP) fell by 4.7 to 7.3 percentage points in the quarter after demonetisation.

A recent Reserve Bank of India (RBI) study further suggests that demonetisation caused a “decline in the already decelerating credit growth of the MSME (micro, small and medium enterprises) sector”. The same report also highlights how GST implementation hindered MSME sector’s exports.

Apart from GST and demonetisation, the government’s zeal in raising tax revenue is also reflected in increased cesses and surcharges, which are not shared with states. The focus on taxation may seem excessive, as contrary to popular opinion, India is not necessarily a tax evading nation. India’s tax to GDP ratio is respectable among developing countries, when adjusted for income levels, as a previous Plain Facts story has pointed out.

Despite all these efforts, fiscal deficit for 2018-19 is likely to overshoot the targeted 3.3% of GDP given downbeat GST collections, disinvestment proceeds and limited scope to further tax petroleum products. A recent note by Upasna Bhardwaj, Suvodeep Rakshit and Avijit Puri, economists with Kotak Mahindra Bank, pegged the FY19 fiscal deficit at 3.5% of GDP, after factoring some reduction in government’s planned capital expenditure.